So much of this is contrary to what we expect in modern buildings. In more modern construction (anytime post 1920 in the main), one wants to waterproof the underfloor completely with plastic and cement, and keep the interior completely insulated and heated. Old houses like this one however, with thick stone walls, need to be able to "breathe," letting water vapor escape through porous materials like lime in the bottom floor and walls. Otherwise, moisture will creep around the waterproofing and cement below and go up into the stone walls, where it will encourage fungus and other deterioration.

After several discussions with our builders about these issues and many hours spent studying UK and French websites about conservation and restoration methods for old stone houses, I finally found a website that seems to explain all of this fairly well (in French). "Maisons Paysannes de France" is a website dedicated to helping owners and builders understand how many of the older houses were built, and how they can be sympathetically updated to improve their functionality without jeopardizing the stone or columbage they were built with. http://www.maisons-paysannes.org/maisons-paysannes-de-france/bienvenue/ and http://www.maisons-paysannes.org/restaurer-et-construire/fiches-conseils/ (the latter providing specific advice about insulating an old structure for better heat retention without damaging it).

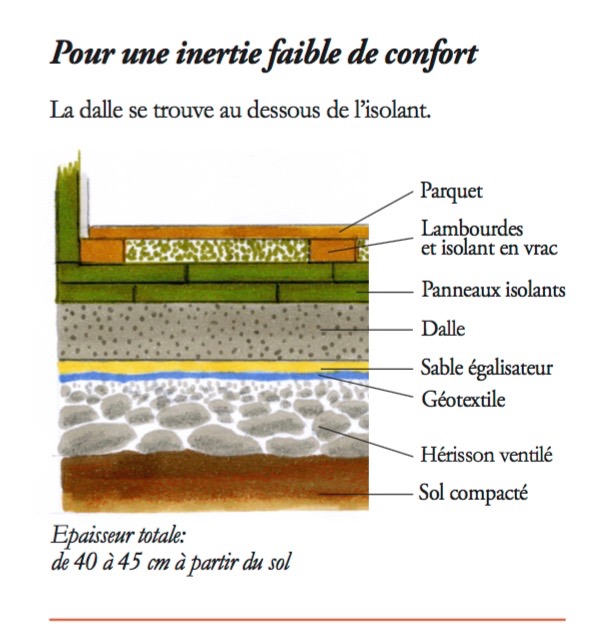

I highly recommend it to any of you who are thinking of renovating a place built before the early 20th century, or who just are interested in architecture and engineering. Those of you who are more clever with Google Translate than I am may even find a way to get most of it into English. I've tried, but the builders' terms don't translate very well. For example, the layer of stone that goes down first on the compacted earth is known as the "hérisson," a term of art. The literal meaning of hérisson is "hedgehog" though, so if you go by Google Translate, it will be telling you to lay down a layer of hedgehogs before you do anything else.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed